If Financial Inclusion is such a big deal, why are so many left out?

I explore six key barriers that at least partially help us understand why

This is part of a series of posts about our mission to support financial inclusion for small businesses at Vaya in partnership with our VSaaS customers. You can find the series along with our other thoughts on embedded fintech at embedvaya.com/blog. If our work resonates with your or someone you know, please check out open roles at embedvaya.com/joinus.

If you’d asked me a few years ago, I would have struggled to come up with any good reasons to avoid the formal banking system. Carrying cash around didn’t make any sense and opening a bank account was pretty easy. There were plenty of banks branches in New York City where I was living at the time. I showed up with my driver’s license, met with a teller, signed some paperwork and got my debit card and that was that.

When I moved to India a few years ago and tried to do pretty much the exact same thing, it proved to be a much harder. I showed up at a bank branch and spoke to me in Kannada the local language here in Bangalore. That was a problem which eventually got sorted out — plenty of English speakers here. Then they asked for ID which was harder because they didn’t recognize my ID from the US. Then we got to proof of address, and … you get the idea. It took forever and the whole time this was going on I was paying for everything in cash withdrawn from my American bank account which meant I was getting hit with a bunch of fees.

Ironically, during this time I was the head of credit for a tech start up and interacting with local bank execs as a part of my job, and one of them was able to help me sort this out. Without an intervention like that, I probably would have just said forget it and gotten on with my life outside the formal system. My co-founder Ankit had a similar experience in reverse while getting set up in the US when he emigrated there. But you don’t have to be an immigrant to have this experience shared by a fifth of Americans.

Around 20% of Americans are financially excluded in some form or the other. What's going on here? If financial inclusion is such a big deal, why are so many on the outside looking in?

In exploring this question, I came across six key barriers that I’ll cover below. As you'll see, the six barriers somehow don't add up to a totally convincing explanation for me, so I'll offer a 7th explanation that I think is at the heart of what's going on here in my next post. I share these with the idea is that if we can understand the problem better, maybe we’ll have better luck in trying to solve it.

Six Barriers to Financial Inclusion - An Overview

Let's start with an overview.

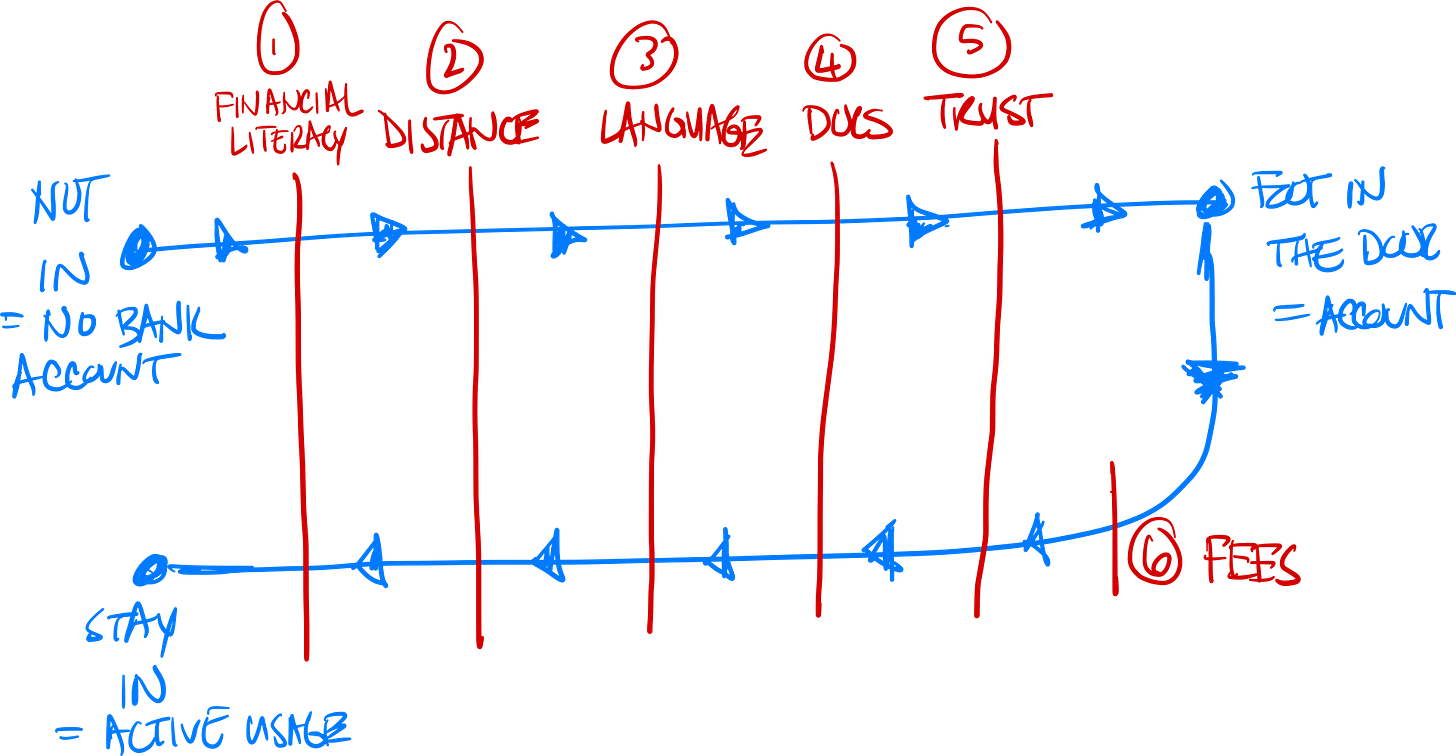

They way I think about the barriers is from the perspective of someone who at home and making their way to getting started with a Bank account. Then I imagine them becoming active users accessing bank services regularly over time. That journey might look like this image below though of course the journey is not likely to be linear in the way I've drawn it and the barriers are not really separate. They often work together to compound the effect.

1. Financial Literacy

Every so often FINRA or the Federal Reserve go through the country and ask people a set of questions on foundational financial topics like compound interest, inflation, risk diversification, bond prices, and mortgage payments. How people answer these questions indicates their level of financial literacy [^1].

I start here because we know that how well people understand these basic concepts is directly correlated with how well they manage their day to day financial lives by which I mean things like paying credit card bills, having emergency savings or investing for retirement [^2]. Unfortunately the results of these surveys indicate only about 30-35% of Americans are financially literate.

I think mainly because most of us are never formally taught these concepts in school [^3]. Whatever, the reason may be, the point is that a lot of people are just not that comfortable with financial products and services and may not understand the cost, benefits and risk of using or avoiding them.

2. Banking Deserts, Distance and the Digital Divide

Let's now suppose that you're financially literate enough to know that you should probably get off the couch and make your way to a bank to get started.

Turns out that it's not always easy to get to a bank branch, especially for low income and majority-minority communities[^4]. The distance might be enough of a barrier to keep some folks out of the formal system.

If you look at the numbers, the number of branches in the US has been declining over the last 15 or 20 years and many people now find themselves in what are called banking deserts where they have to basically travel twice as long -- something in the range of 10 plus miles to get to a bank branch in contrast to the median of 5 miles.

The obvious rebuttal here of course is that around the time the bank branches started to decline is also about the time when smartphones started to appear and a lot of people shifted their banking interactions online. I won't have time here to get into the details of what's driving branch consolidation in the US, but the short of it is that the regulatory environment changed in the late '80s. This "deregulation" allowed banks to optimize for profitability rather than coverage. [^5]

One problem is that around ~15% of Americans are on the wrong side of the digital divide -- they don't have a smartphone or a working internet connection. This number is closer to 30% for low income communities [^6].

Even aside from the digital connectivity issue, there is something very important about the face-to-face interaction and the soft knowledge that accrues to the people that are working their local branch. As we all learned during covid, an IRL meeting is different than any other alternative.

In person relationships are especially important for small businesses trying to access credit. Turns out whether or not they're successful in getting a loan often depends on the relationship they have with somebody at a local branch manager and the soft information they have about the business owner and their specific business context.

Research from the Fed finds that if a branch closes it actually depresses small business lending in that area for nearly a decade, even if other branches later come back later because the soft information is lost when the branch closes and it takes time to accumulate again [^4].

3. Language Access

Now suppose that you make it to the bank only to find that really the language that you are most comfortable in is not the language that the person at bank greets you in.

This may seem like a marginal problem, but the practical reality is that that in 22% of Americans speak a different language than English at home [^7].

Mind you that it doesn't have to be a complete language mismatch for this to be a barrier for somebody. Imagine a Spanish speaker who gets by in English, trying to navigate a banking interaction. Or an English-speaking bank teller who has some high school Spanish, trying to navigate this interaction on the other side. Just the nature of talking about financial subjects – especially if there is a financial literacy gap already – it's just difficult unless both sides are fairly proficient in the language they are commonly speaking.

4. Documentation

Of course you can't open a bank account without being able to prove who you are and where you live. Believe it or not, this ends up being a big deal for a lot of Americans.

It turns out that nearly half of Americans don't have a passport and some 70% or so don't have a drivers license [^8].

These are typically the documents you'd use to prove your identity. If you're not an American, even if you are legally here, there are a whole other set of documents that you may need to provide that could be onerous enough to turn you away.

5. Trust and Peer Effects

Trust is a big deal for banks after all their whole business model is predicated on you handing them your hard earned money with the assurance that you can get it back later. Hence the banks as vaults facade on branch buildings.

As you can imagine then, if it's painful to get to a branch and talk about a complicated subject in a language that you're not comfortable with either -- none of that is helpful for implicitly building trust.

This trust problem is further exacerbated by the fact that people are social creatures and peer effects have a big impact on their decisions generally and for their financial decisions particularly [^9].

In other words, it's not just that you have to have a difficult experience with banks for them to impact you, it's enough that somebody you know in your community and to have a bad experience with the formal financial system for that to mistrust to catch you by contagion.

Unfortunately, there are many communities that have indeed had poor experiences with the formal financial system in the context of American history. Stories of disrespect, exploitation or outright discrimination are not difficult to find [^10]. In fact an alphabet soup of legal frameworks that exist to this day like the Truth in Lending Act -- usually called "Reg Z" -- or the Fair Housing Act (FHA) or the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA) among were all put in place to prevent such practices. Nevertheless, some communities have developed a healthy mistrust of banks and have concluded concluded that their business is simply not welcome.

6. Fees, Rationality and Impermanent Inclusion

Let's say someone makes it over the line and opens up a bank account -- is that the end of the story? Unfortunately not.

As it turns out, financial inclusion is a fluid, impermanent state [^9]. Some folks with accounts stop using them. Others use some services but still rely on informal or third party services for others.

Maybe they use their account for savings, but not for payments choosing more convenient modern apps instead. Or they would consider a loan from their bank, but for sending money to family abroad, they'd rather use something else.

It might be tempting to assume that all of this complexity and behavior is random, but what we find is that people make decisions to use formal financial services or use some and not others pretty rationally. And they consider many of the barriers we have already covered on an ongoing, service by service basis to make decisions [^9].

One additional factor that only applies once they are in the system are fees. Banks charge fees for all kinds of things: minimum balances for accounts, cashing checks, using the ATM, overdrafts, and on and on.

Many bank fees disproportionately affect low income and minority users [^11]. Half of the underbanked users who used to have accounts but have dropped out point to high bank fees as the main reason [^9].

Wait, Something Doesn’t Add Up…

These six reasons we've covered made sense, and I could easily imagine them on their own or in combination with the others presenting significant barriers to financial inclusion. But something about them didn't quite add up for me.

After all, businesses, including startups, are constantly solving for barriers that stop potential customers from using their product.

It seems to me that if the bank wanted to solve for any or all of these six problems, they should be able to do. So the question is, why aren't they just doing that? I think there is one root cause here, and I'll dive into that in the next post.

Footnotes

[1]: See FINRA's 2022 Report on Financial Capabilities here. The Fed's Report is here. If you are curious to see what these questions look like, see the survey questionnaire here.

[2]: From the Finra Report.

[3]: See this analysis by Annamaria Lusardi at Stanford on the importance of financial literacy based on the Fed's data. She has a lot of work on this topic so google her for me if you're interested.

[4]: From this article by the NY Fed from 2016.

[5]: If you are interested in learning more about this, I'd recommend reading a book called How the Other Half Banks by Mehrsa Baradaran. Harvard University Press, 2015. It's by far the best book that I've read on the evolution of banking in the US with an inclusion lens.

[6]: This article from the Pew Research Center, 2021.

[7]: U.S. Census Bureau Data. “American Community Survey: DP02 | Selected Social Characteristics in the United States,” select “2021: ACS 5-Year Estimates Data Profiles.”

[8]: https://www.ifac.org/knowledge-gateway/preparing-future-ready-professionals/discussion/financial-inclusion-through-digital-inclusion

[9]: From this paper titled The Underbanked Phenomena by Xioyan Xu, 2019.

[10]: See Xu 2019 (Footnote 9) on how many underbanked referred to the quality of service, trust and respect as reasons to choose alternate financial services over traditional banking. This analysis by the Atlanta Fed from 2018 focuses on the experiences of minority owned firms. The historical experience of African Americans in obtaining credit for housing is a particularly harrowing one -- this NY Times article provides the broad strokes of how problems persist into modern times.

[11]: See this article from the Georgetown journal on Poverty Law and Policy from 2021 and this one from Harvard Business School in 2022 specifically talking about overdraft fees.